African Masks from Various Cultures - Part 1

ADVERTISEMENTS

| ||

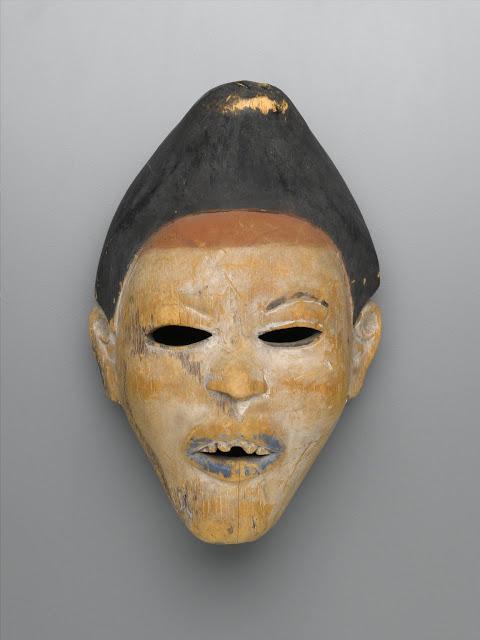

| Kongo Mask - 19th Century Kongo Central Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo This mask was worn by a Yombe nganga, or ritual expert. Its white color probably represents the spirit of a deceased person. White was also associated with justice, order, truth, invulnerability, and insight—all virtues associated with the nganga. Gelede Mask - Yourba Culture Nigeria, Late 19th or Early 20th Century Gelede masks, such as this one, are worn by male Yoruba dancers at festivals honoring the women of the community, living and dead, especially the powerful Great Mothers, including both the elderly women of the community and the ancestors of Yoruba society. The gelede performances entertain and educate, and document elements of everyday life, such as the woman’s head tie in this example. Through their movements, gelede dancers express Yoruba ideals of male and female behavior. 19th century African Mask. Probably made in Gabon or Republic of the Congo. Mblo Portrait Mask , Baule Culture, from Lacs, N’zi Comoe, or Valle du Bandama Region, Ivory Coast, Late 19th-Early 20th Century Helmet Mask (ndoli jowei) for Sande Society, Mende Culture, from Guinea or Sierra Leone, 19th Century The ceremonies of the Sande society are the only occasions in Africa in which women customarily wear wooden masks. Masks like this one represent the society's guardian spirit at public events such as funerals or the installations of chiefs.The features of the mask illustrate the group's ideal of feminine beauty, with a broad, high forehead, small narrow eyes, and an elaborate coiffure. The elegant hairstyles also symbolize the importance of social cooperation, since a woman needs the help of her friends to dress her hair. In Sierra Leone and western Liberia, each town has a Sande society that includes all of the women in the community. It represents them and binds them together as a powerful social and political force. The Sande society is one of the most influential patrons of the visual arts in West Africa. Mask for Okuyi Society (Mukudj), Punu Culture, from Gabon, Late 19th or Early 20th century Mask for the Okuyi Society (Mukudj) - Punu Culture, from Gabon, Late 19th Century The mask’s white coloring symbolizes peace, the afterlife, and the spirits of the dead—though today its performances are chiefly for entertainment. Bush Cow Mask, Bamenda Culture, from Bamenda, Cameroon, Late 19th Century Mask (Mbuya) of Chief (Phumbu), Pende (Western) Culture, from Democratic Republic of the Congo, late 19th-early 20th century Bwoom Mask, Bushoong Kuba Culture, from Lulua Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo, late 19th or early 20th century Kuba mythology revolves around three figures, each represented by a masquerade character: Woot, the creator and founder of the ruling dynasty; Woot’s spouse; and Bwoom. Bwoom’s specific identity varies according to different versions of the myth. He may represent the king’s younger brother, a person of Twa descent, or a commoner. Embodying a subversive force within the royal court, the Bwoom masquerade is often performed in conflict with the masked figure representing Woot. Wan-pesego Mask, Mossi Culture, late 19th or early 20th century Banda Mask, Nalu or Baga Culture, from Guinea, late 19th or early 20th century This mask combines human features and those of a crocodile or shark with teeth bared. It has the tail of a chameleon, the horns and ears of an antelope, and features of less identifiable animals. Worn horizontally on top of the head, the mask is attached to a skirt of vegetal fibers that covers the body of the wearer. Banda masks were the property of the Simo men’s society, which historically oversaw and regulated fertility and initiation ceremonies. Today it is danced primarily for entertainment. Kuma Mask, Bobo Culture, from Burkina Faso, late 19th-early 20th century This mask blends features of a hornbill bird, or kuma, with the horn of a buffalo, or tu, combining animals associated with great wisdom and danger. Men wearing such masks perform at the initiation rites to men’s societies, at the funerals of important male elders, and at annual harvest ceremonies. The fact that this mask has only one buffalo horn may indicate that its design was transferred between clans, in which case the original form, with two horns, would have been slightly altered. Komo Society Mask, Bamana Culture, from Ségou, Koulikouro, or Sikasso Region, Mali, late 19th-early 20th centuries Bamana masks such as this one are worn and seen only by members of the Komo association, whose members harness the power (nyama) contained in the mask to aid members of the community. Powerful materials—including blood, chewed kola nuts, and millet beer—are applied to the mask, while prayers and sacrifices are offered. The open mouth and the horns, tusks, and porcupine quills symbolize the Komo’s power to punish those who violate its rules. Mask (Karan-wemba), Mossi Culture, from Nord Region, Burkina Faso, 19th century The female figure atop this mask represents a married woman who has just given birth to her first child—a moment when a woman is considered to be the most beautiful by the Mossi. Such masks are danced at burials and celebrations to honor the spirits of deceased female clan elders. Female Kifwebe Mask, Songye Culture, from Tanganyika Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo, late 19th or early 20th century The kifwebe masquerade is a genre shared by the Luba and Songye, indicative of the interaction that has occurred between the two societies. Kifwebe masks represent either male or female beings. Both mask types are characterized by angular and thrusting forms, and in both cases the entire face is covered in patterns of geometric grooves that are uniquely characteristic of these masks. Female masks, such as this one, are distinguished by the predominant use of white clay and the rounded form of the head crest. Dean Gle Mask, Dan Culture, from Ivory Coast or Liberia, late 19th-early 20th century Historically, Dan society vested political leadership in a council of elders. Masks served as agents of social control, enforcing the council’s rules and orders. The masked figures were believed to be incarnate spiritual beings capable of rendering unbiased judgments. The specific functions of individual masks, once removed from their village contexts, are impossible to determine. Here, the nearly closed eyes and small mouth contrast with those of other masks and probably indicate that this example served in a peacemaking function and generally created harmony in the community. Male Face Mask, Fang (Betsi subgroup) Culture, from Gabon, 19th Century Little is known about the functions of masks such as this one, since they fell out of use by 1910. It is thought that they might have had a role in boys’ initiations into adulthood.Among the Fang, the spirits of the dead are associated with the color white, suggesting a connection with the ancestral realm. White clay (kaolin) is also used by healers in medical practices. This face mask could have been related to either set of practices. Mask with Hinged Jaw (Bu Gle), Dan Culture, from Liberia, 19th Century Source: brooklynmuseum.org | ||

ADVERTISEMENTS

| ||